Understanding Human-Centred Design

Human-centred design is a framework that emphasises the human perspective in all steps of the design process. It serves to provide the end user with a product that they will truly want, need and find useful. It is also often seen as something more than just a design framework: it is a mindset and a tool that intends to create a long-lasting, positive impact on the user.

According to IDEO.org, the approach to human-centred design consists of 3 phases: Inspiration, Ideation and Implementation.

[Image taken from ideo.org]

Inspiration: The aim is to learn and truly understand exactly what the user needs. There are a series of steps that designers follow in this phase that enable them to deepen their understanding of the requirements for the project:

Ideation: This gives the designer the opportunity to make sense of their findings, draw meaning from them, and prototype potential solutions. This can again be broken down into a series of straightforward steps:

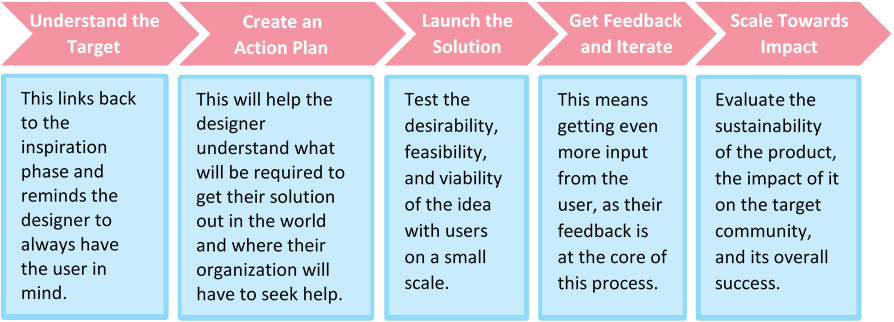

Implementation: This is the phase that brings the solution to life. By following a co-design process with the people involved, the solution is more likely to be something they utilise and hold agency over. The steps are as follows:

It is clear to see that this has all the makings of a successful method. The process of iterating and continuously developing and adjusting ideas for the benefit of people leads to enhanced user satisfaction, which leads to greater success for the business. There are numerous examples, in different industries, of this working in the favour of both the business and the consumer. Recently, companies such as IKEA and Apple have chosen to focus on the emotional relation between their products and the consumer, rather than focusing purely on technology.

A proponent of this approach is Tricia Wang, a ‘global tech ethnographer’. She focuses on ‘thick data’ (small-scale qualitative, human-centred data) rather than ‘big data’ (large-scale, quantitative analyses). She believes that thick data, though smaller in scale, is crucial in finding out what users truly want or need. Whilst big data can be useful to uncover patterns, it is thick data that provides context and detail to these patterns. Therefore, she believes integrating the quantitative approach and the human-centred approach can yield the best results.

This is not to say that human-centred design does not come with its drawbacks. It has often been criticised for stifling true creativity. It has also been argued that this type of design does not push boundaries, as it only attempts solve to present-day problems instead of thinking ahead.

Human centred design is particularly important in the developing world, hence our adoption of it at InAGlobe. By liaising with stakeholders on the ground, we can understand what it is that communities truly need and practice inspiration alongside them. With contextual constraints in mind, we can hand over projects to academics at Imperial, and other universities to carry out the ideation and implementation phases. In particular, two of these projects involve human-centred design: a mathematical brailler for unlocking numeracy and a pill-organiser to facilitate self-medication.

The first is a project proposed by Kilimanjaro Blind Trust, operating in East Africa: an electrical brailler that includes a series of design constraints that will allow visually impaired children to unlock their abilities in STEM. Currently, numeracy levels amongst VI individuals is low because the focus of their education surrounds a braillers that tackle literacy. A user-centred approach has been taken to cater for the specific needs of visually impaired children, and for the educators such that the device can be easily integrated in their current educational practice. This ranges from the inclusion of mathematical symbols to various refreshing working lines or affordability and energy requirements.

Meanwhile, the pill-organiser has been taken up by a final year MEng Biomedical Engineering student and is currently undergoing prototyping cycles. This involves mapping the user needs: understanding that young adults and children are the main focus, and therefore predicting the conditions the pillbox will be exposed to and how this affects engineering constraints. For instance, clear audio feedback is crucial for blind children.

Both projects directly reflect the needs of communities in developing countries, and we hope that their implementation can have a long-term, positive influence on the lives of those affected by the issues.

Human-centred design is a process that we advise anyone working in any form of interface with users to incorporate, so that the usability can be as smooth and relevant as possible. It will allow entrepreneurs to adjust prototypes accordingly before great investment is made, and improve the experience of stakeholders. There are many resources out there which can be utilised for free, ranging from courses on +Acumen or tool kits on https://www.ideo.org/ and https://movestheneedle.com.

Written By: Kavya Ganabady (23/04/2019) - Outreach Volunteer of InAGlobe Education.

Resources

https://medium.com/ethnography-matters/why-big-data-needs-thick-data-b4b3e75e3d7https://movestheneedle.com

For more information on Tricia Wang, see her TedTalk: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pk35J2u8KqY